How do we decide on the merit of a writer? A leitmotif of The Truth about Art is that every work of art starts from previous works, so that if we compare the later creation with its models, something of the quality that guided the artist might move us. The passage below comes from a discarded section of TTAA.

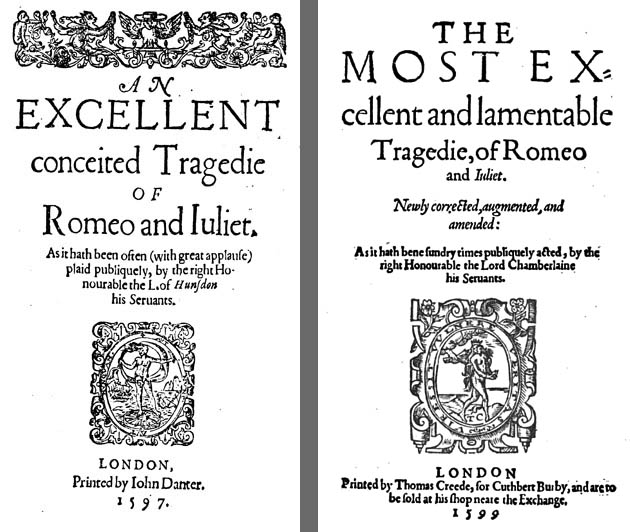

William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet; left, frontispiece of 1597; right, frontispiece of 1599. The typography of the earlier frontispiece exposes the lamentable quality of the later one.

Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet was first printed in a pirated edition of 1597, with the title ‘AN EXCELLENT conceited Tragedie of Romeo and Juliet…’. Two years later, a ‘good’ quarto was published to chase away the bad one, announcing itself ‘THE MOST EXcellent and lamentable Tragedie, of Romeo and Juliet…’ (see above). What might contemporaries have found ‘most excellent’ in this play?

Before Shakespeare wrote, Italian, French, and English variants of the story were already well known. Shakespeare took most from a long poem by Arthur Brooke, The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet (1562). If we hold extracts from the last act of the play against the equivalent passages in Brooke’s poem, Shakespeare’s excellence might move us.

Brooke’s Romeus descends into the Capulet tomb:

And then with piteous eye, the body of his wyfe

He gan beholde, who surely was the organ of his lyfe [Romeus and Juliet, 2632]

Should we chant Brooke’s lines in a sing-song? Against these rhymes, Shakespeare’s blank verse sounds utterly natural, so we should recall how fluent and rhythmic was the language of his Roman histories compared to Thomas North’s rendition of Plutarch, where he found the material (TTAA, pp. 61–62). Brooke is also prolix. Having beheld his wife and ‘watred her with teares’, Romeus took his poison; declaimed to Juliet about their sacrifice; saw ‘bold Tybalt’s carkas dead’, to whom with outstretched hands he cried for mercy; said his prayers ‘kneeling upon his knees’; and 45 lines after the fatal ingestion, his ‘long imprisoned soule hath freedom wonne at length’.

Shakespeare’s drugs were more effective:

Romeo: …Here’s to my love.

He drinks the poison.

O true apothecary,

Thy drugs are quick! Thus with a kiss I die.

He kisses Juliet, falls, and dies. [Romeo and Juliet, 5:3:120]

Romeo had prudently made his speech in the tomb before taking the poison. He delivered all Romeus’s material in just 27 short lines, and introduced a notion apparently adapted from the final speech of Brooke’s Juliet. Brooke had thought it necessary for Juliet to explain her suicide to the dead Romeus.

Receive thou her, whom thou didst love so lawfully,

That causd (alas) thy violent death although unwillingly;

And therefore willingly offers to thee her gost,

To thend that no wight els but thou, might have just cause to boste

Thinjoying of my love, which ay I have reserved,

Free from the rest, bound unto thee, that hast it well deserved… [Romeus and Juliet, 2787]

This is how Shakespeare transformed Brooke’s banal conceit and clumsy doggerel in Romeo’s restless imagination. First his Romeo addresses Tybalt, then he turns to Juliet:

Forgive me, cousin! Ah, dear Juliet,

Why art thou yet so fair? shall I believe

That unsubstantial death is amorous,

And that the lean abhorred monster keeps

Thee here in dark to be his paramour?

For fear of that, I still will stay with thee;

And never from this palace of dim night

Depart again: here, here will I remain

With worms that are thy chamber-maids… [Romeo and Juliet, 5:3:109]

These images are vivid and particular, and they are urged forward by the beat of the unobtrusive verse. When her time comes, Shakespeare’s Juliet is as forthright as his Romeo:

What’s here? a cup, closed in my true love’s hand?

Poison, I see, hath been his timeless end:

O churl! drunk all, and left no friendly drop

To help me after? I will kiss thy lips;

Haply some poison yet doth hang on them,

To make die with a restorative.

Kisses him

Thy lips are warm.

First Watchman: [Within] Lead, boy: which way?

Juliet: Yea, noise? then I’ll be brief. O happy dagger!

Snatching Romeo’s dagger

This is thy sheath;

Stabs herself

there rust, and let me die.

Falls on Romeo’s body, and dies [Romeo and Juliet, 5:3:169]

Of course we have been unfair to Brooke, leaving the archaic spelling, and comparing his prosaic patter to its transformation in the mind of the language’s most sublime poet. If we were judging Brooke, we should need to discover his models, and see what he has made of them. Yet Shakespeare took so much from poor Brooke: his plot, his sub-plots, his characters, individual incidents, his very words! From such dross did he fashion the limpid clarity of his verse and have us relive the heartache of teenage love. Listen to the jaunty jingle of Brooke’s ending, then to the spare pathos of the words that Shakespeare leaves echoing in our ears:

And even at this day the tombe is to be seene,

So that among the monumentes that in Verona been,

There is no monument more worthy of the sight,

Then is the tombe of Juliet, and Romeus her knight. [Romeus and Juliet, 3020]

For never was a story of more woe

Than this of Juliet and her Romeo. [Romeo and Juliet, 5:3:309]