Chapter Five: Sublime

‘We must begin by raising the question as to whether there is an art to loftiness or profundity. For some think that those who try to reduce it to technical training are wholly deceived. A great nature, they say, is born gifted, and not formed by teaching. Works of natural ability, so they think, are spoiled and utterly demeaned by the dry impoverishing rules of art.’ —Longinus, On the Sublime (first century CE)

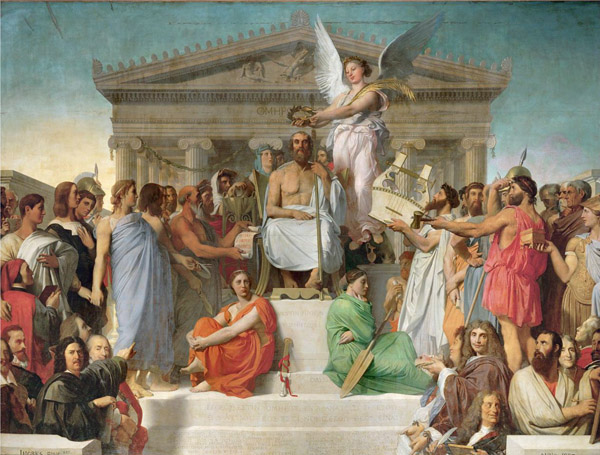

A dialogue between ancient and modern attitudes to Art has long been thought impossible, since the ancients knew nothing of our modern addiction to genius, originality, rule breaking and self-expression, or capturing the spirit of the age. By recognising Quality [virtù, aretê] as the means by which we adapt an inherited tradition to new circumstances, we realign ourselves with the deepest roots of our culture, which reach back to the godlike conduct of Homer’s heroes (fig. 5.1).

One impediment to this process has been the assumption by both Plato and Aristotle that an art could be described, so that it became a branch of knowledge. That philosophical spell was broken in 1674, when Longinus’ treatise On the Sublime was translated into French (fig. 5.2). This late antique work of literary criticism insisted that the description of an art was technologia, but any attempt to capture the sublime with words would destroy it. At a stroke, this observation destroyed the assumption that an art was bound by rules that could be found in books.

Fig. 5.1, Ingres, Apotheosis of Homer, 1826–33, Paris, Louvre. The seated Homer is crowned with a victor’s wreath, while his creations, a blood-red Iliad and a sea-green Odyssey, sit at his feet. On either side poets, painters, sculptors, and orators look to Homer for guidance, with only Plato (on our right) turning away from him.

Chapter 5 on the sublime begins by restating the old rules of art, so that readers may relive some of the excitement felt by artists and critics when they found themselves allowed to discard them. These rules include linear perspective in painting; ideal proportions for the human body; the enduring myth of the Golden Section; the rules of classical architecture; and the stipulations for stage tragedy derived from Aristotle’s treatise on poetry. All these rules were cast to the wind after late 17th century critics read Longinus, who recorded the ancient belief that the loftiest value in literature will not be bound by rules.

By 1700 Longinus’ views on the sublime had been transferred from poetry to painting. Now an elevated esprit who discarded the rules of drawing stood on the firm foundation of ancient authority. The 18th century doctrine of Genius followed immediately.

Fig. 5.2, detail of fig. 5.1: the bearded Longinus turns to Homer for inspiration while writing On the Sublime; below him, a periwigged Nicholas Boileau reads Longinus’ Greek text before penning his French translation.

< Previous Chapter | Next Chapter >